Have you ever seen leaders make a call that you’re sure was the wrong choice?

Considering that the average executive makes 70 decisions per day (says Professor Sheena Iyengar of Columbia Business School), some mistakes are inevitable. But what if companies could introduce collaborative systems that help leaders make better decisions? If we can raise the aggregate quality of leadership decisions by 10%, how might that impact company performance?

McKinsey research found that for big-bet decisions, high-quality debate led to decisions that were 2.3 times more likely to succeed. Yet most executive meetings still operate on feel and gut – over-relying on smart people in a room, and under-utilizing systemic rigor and analysis.

Some companies have built decision-making processes and structures that can improve leaders’ decisions. Amazon is one such example, where their “six-page memo” has become globally recognized, and contributed to their record as the fastest company to reach $100B in sales in the world (taking only 22 years).

But Amazon is the exception to the rule. Most companies haven’t built a strong process fortifying how leaders make strategic decisions. Below, we outline the potential pitfalls that result when there’s a lack of rigor applied in this process.

Cognitive Vulnerabilities Are Hiding in Plain Sight

Poor decision-making is rarely the result of a single error in judgment or a lack of intellect. It’s a systemic failure that allows cognitive biases to go unchecked. We all have them, but they’re so prevalent in our thinking that they can be hard to recognize.

At the individual level, leaders fall prey to predictable patterns. The planning fallacy causes executives to consistently underestimate time, costs, and risks while overestimating benefits. As a result, “best-case” scenarios often get presented as base-case realities to secure funding. When leaders are shopping around ideas, they can easily fall prey to confirmation bias that validates their existing beliefs, discounting signals that challenge their worldview. And once they’ve secured buy-in to move forward, reversing course becomes extremely difficult because of the sunk cost fallacy, which keeps leaders investing in failing projects and prevents capital from flowing to higher-growth areas. These aren’t personality quirks, they’re predictable deviations from rational judgment that all people are susceptible to.

Group dynamics compound these individual vulnerabilities, and introduce different sources of bias. Groupthink for example causes cohesive teams to prioritize consensus over the accurate assessment of alternatives. In corporate boardrooms, this is made worse by hierarchical structures where challenging more senior executives can carry political costs. Without structured dissent mechanisms, risky decisions can get rubber-stamped as those with dissenting views stay silent to avoid appearing difficult. The pressure to stay consistent, project confidence, and achieve consensus creates fertile ground for miscalculations in any organization.

When Bias Scales: Case Studies in Corporate Collapse

It only takes a few leadership errors to sink a business. Consider the examples below, where a few biases ended in spectacular failure.

Kodak’s leadership thought of their business as “chemical imaging,” rather than “capturing moments.” This narrow frame blinded them to the reality that customers valued the image, not the physical film. Here’s the painful irony: Kodak engineers actually invented the digital camera in 1975, and leadership suppressed the technology to protect their film monopoly. They prioritized protecting existing assets over creating new value. Eastman Kodak shares peaked in 1997 at more than $94 per share… Fifteen years later, the company filed for bankruptcy. One overly narrow view shared the the leadership team was all it took to sink this previous Fortune 500 company.

The Wells Fargo cross-selling scandal of 2016 demonstrates how risky incentive structures can result in poor decisions at scale. The bank set a goal of selling eight products per household, a metric that was mathematically impossible for many regions. When over 5,300 employees were investigated for opening fraudulent accounts, senior leadership blamed “bad apples,” failing to recognize that the system naturally encouraged fraud. Leadership ignored red flags because short-term revenue numbers were positive, a form of “motivated blindness” where leaders fail to notice unethical behavior when it serves their interest. Wells Fargo proves that culture is the output of decision architecture. If incentives for bad behavior (keeping one’s job) outweighs the incentives for good behavior (ethical compliance) – the decision to commit fraud becomes a rational choice for the employee. Had Wells Fargo more carefully considered the second order consequences of placing such aggressive targets, they may have avoided this costly hit to their revenues and reputation.

The Amazon Blueprint: Narrative Over Slides

Jeff Bezos understands the importance of building processes for high-stakes decisions. In 2004, he sent a company-wide email banning PowerPoint presentations in executive meetings. His reasoning was that: “PowerPoint is a sales tool. Internally, the last thing you want to do is sell. You’re truth-seeking… A memo is the opposite.”

In its place, he instituted the six-page memo. Before any major decision, someone writes a narrative document containing complete sentences, logical arguments, and data-backed claims. Meetings start with everyone reading the same memo in silence, which Bezos calls “study hall.” This eliminates the biggest dysfunction in corporate decision-making: people debating from different versions of reality.

Full sentences demand that you show your work: because X, therefore Y, and if Z happens, here’s the plan. Time in the meeting is spent stress-testing ideas rather than watching someone perform with a slide deck. In this environment, charisma gets neutralized, while analytical reasoning gets amplified.

The result is a powerful upgrade in decision-quality that produces better questions, clearer tradeoffs, and an organizational record documenting what was decided and why.

The AI Opportunity: Decision Architecture at Scale

The process Bezos built can now be augmented and accelerated with AI.

AI offers incredible value in helping managers and leaders make more informed strategic decisions. It can analyze historical circumstances and research market realities, generate scenario plans and accurately frame tradeoffs, identify blind spots and challenge assumptions, and pressure-test hypotheses before capital gets committed. It can create decision architecture that ensures tough calls aren’t getting made from gut feelings or the mood in the room.

We built a Decision Operating System inspired by Amazon’s six-page memo, using an LLM to quickly frame choices, contextualize decisions, and forecast potential consequences and next steps. It borrows components of Bezos’ six-page memo, including the long-form framing of options, while adding AI-powered stress-testing that would be time-consuming to replicate manually. What previously would have taken a full day’s analysis to pull together, AI can now assemble in minutes now that this formatting and structure is complete.

When Does a Decision Operating System Add Value?

Not every decision requires this level of rigor. But by building a tool that generates a comprehensive analysis that can be read in 8 minutes – we’ve lowered the barriers to applying rigorous analysis on decisions by any leader or manager. The best moments to lean on one of these tools is below:

Preparing for important meetings. Before walking into a board presentation, an investor pitch, or a strategic planning session – leaders benefit from having their assumptions challenged and their arguments pressure-tested. The Decision Operating System acts as a sparring partner to surface weaknesses in logic before someone else does.

Before making complex or irreversible decisions affecting their teams. Restructuring, role changes, resource allocation; these decisions ripple through organizations in ways that aren’t always visible from the top. The system forces consideration of second-order effects and helps leaders anticipate how choices will land across different stakeholder groups.

Before making large expenditures. Capital allocation decisions benefit from structured analysis that goes beyond the standard business case. The system identifies opportunity costs, surfaces risks the proposal might downplay, and provides a framework for evaluating whether the investment aligns with strategic priorities.

Before making important strategic pivots. Changing direction is expensive. Not just financially but in terms of organizational momentum, team morale, and market positioning. The Decision Operating System helps leaders consider whether a pivot is genuinely warranted or whether they’re reacting emotionally to negative short-term signals.

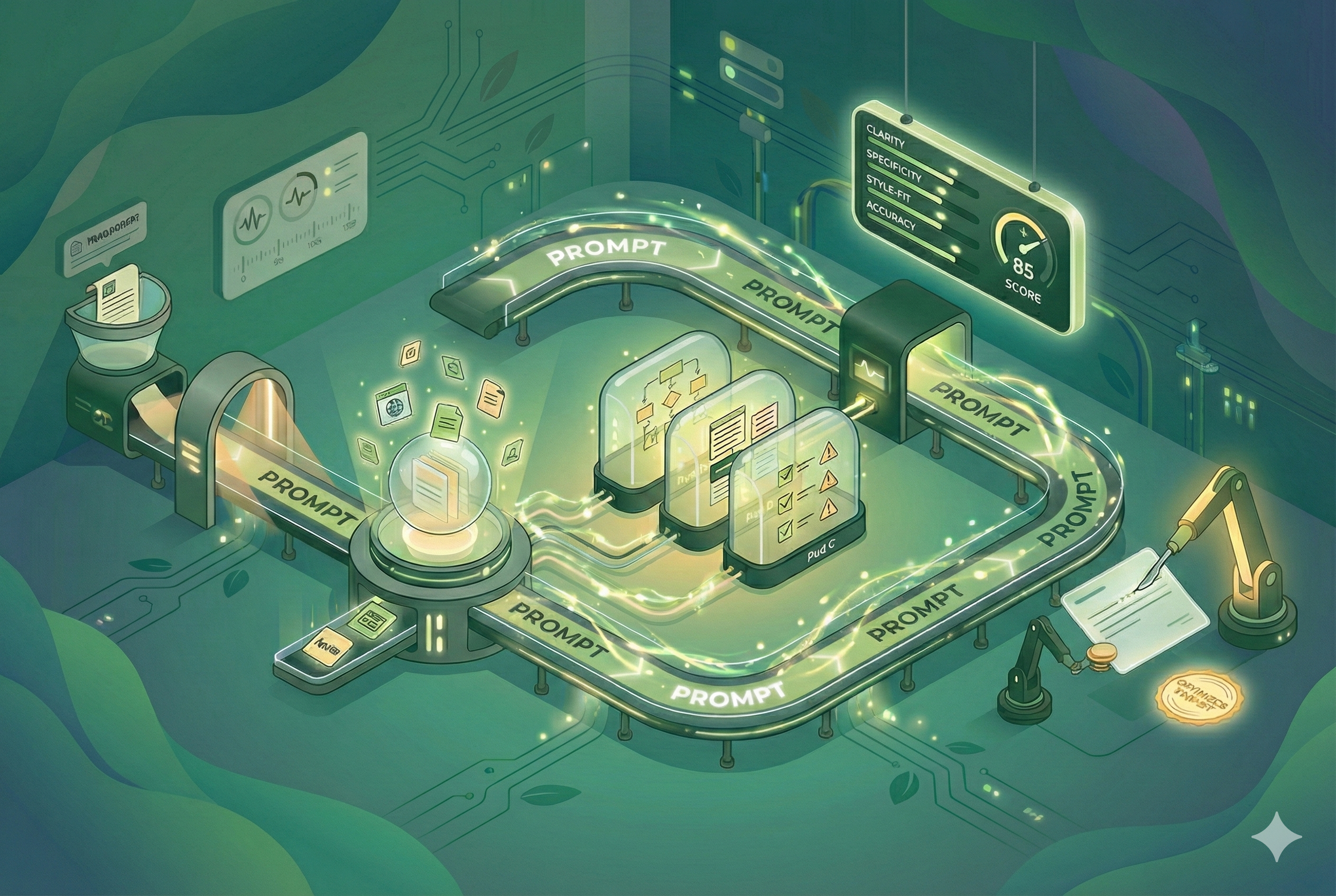

How the System Works

The system starts by first clarifying details about the tradeoff you’re considering. It asks for additional context that you forgot to share in your initial ask like hard constraints (budget and timeline) or other details that would help deliver a more informed decision. By requiring a “PASS” confirmation before proceeding, the system ensures that subsequent debate is grounded in your reality, not hypothetical fluff. It will keep asking questions until all the major considerations are covered.

Rather than trusting AI’s singular opinion on a tradeoff, the system taps the wisdom of crowds by simulating a board debate. One of AI’s unique capabilities is its strength at role-playing, especially for successful public figures with substantial public information about their insights and analytical frameworks. I built a nine-member board comprising some of the savviest business minds across strategy (Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Sheryl Sandberg), product (Paul Graham, Eric Ries, Bob Iger), and distribution (Gary Vaynerchuk, Alexis Ohanian, Neil Patel). This is a carefully curated selection of distinct mental models that can help add diversity of perspective to the output. The design unlocks cognitive diversity, helping to eliminate potential blind spots remain.

The system doesn’t aim for agreement, it actually manufactures friction. In the opening round, each member rates Risk and Upside on a 1-5 scale, generating quantitative data points immediately. Then comes cross-examination, where the prompt forces personas to critique one another, simulating devils’ advocate positions. Scenario planning follows, with members adding preliminary forecasts for success and failure cases. Finally, the board votes – with each board member getting to distribute 11 votes based on their degree of confidence.

Even when a Consensus Plan wins, the system generates a Minority Report logging dissenting views. If Bill Gates and Neil Patel vote “No,” you know specifically that your tech stack and SEO strategy are at risk, even if the Board votes “Yes” overall. This replaces the echo chamber of a single mind with a simulated adversarial network. It turns the solitary act of decision-making into a team sport, without the scheduling conflicts.

Beyond the Decision: Planning for What Comes Next

Simply choosing between options doesn’t prepare executives for what happens after. Most bad decisions aren’t made because the initial strategy was wrong, they’re made because leaders stayed on the initial strategy too long after circumstances changed. In the heat of battle (leads dropping, cash burning), emotion can cloud judgment. It’s easy to say “let’s give it one more month,” even when data is screaming to “Stop.”

The Dynamic Playbook maps out the base case (what we expect to happen), the bear case (what to do if our strategy fails), and the bull case (how to respond if outcomes exceed expectations). Most importantly, it defines trigger conditions when we should consider changing course. This contingency planning makes the “when to switch” decision easier and helps executives anticipate necessary changes before crisis mode sets in.

Finally, a Second Order Consequence Scanner examines systemic ripple effects. Most bad decisions happen because we solve for X but break Y (for example optimizing for efficiency, but breaking customer trust). This feature forces the Board to look beyond the immediate decision and identify ripple effects before they become fires to fight.

The Dashboard: Decision Intelligence in One View

A strong sequence is good. But a dashboard deconstructing the decision is better.

The system outputs a single dashboard comparing two choices and delivering rich context on both options: highlights from the simulated debate, dual scenario illustrations for bear and bull cases, second-order consequences and opportunity costs, and trigger points indicating when to change course. In just 8 minutes, leaders can read and get impressive visibility into the opportunities, risks, and consequences of each respective choice.

The Compounding Returns of Better Decisions

Here’s an example run I did with a challenging decision sales leaders might be contemplating in their strategic plan: Should I double down on my ICP, or try to expand into new markets that are showing some traction? Below is a structured analysis of this tradeoff that can help an executive (or even middle manager) reason through these competing strategies:

Research at the University of Ohio concluded that 55% of executives prefer ad hoc methods over any formalized decision process, while 50% rely heavily on intuition rather than analysis. It also showed that thirty percent of the time, poor decision-making structures were the cause of failed decisions.

The opportunity isn’t incremental, it’s transformational. The technology exists to move businesses from “feel” and “gut” to sober, carefully considered analyses. From “smart people in a room” to “clear decision systems.” From echo chambers to structured dissent.

Clean processes beat raw IQ in messy, high-stakes environments. The Decision Operating System is tool that can help us get there.